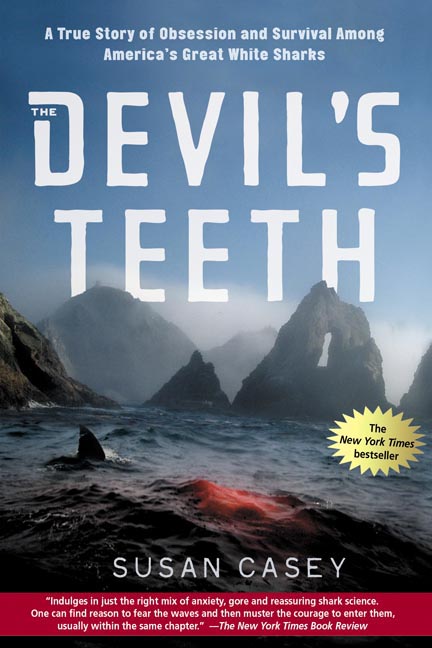

The Devil’s Teeth

by Susan Casey

Henry Holt 2005

First edition, hc

14pp color photo insert

Frontispiece map

Selected Bibliography

Twenty or so miles beyond the Golden Gate Bridge but still within San Francisco city limits lie the Farallon Islands. They are another world entirely. Wild, wind- and sea-battered, and desolate, they host sea birds, sea lions, walrus, and bird lice. Mosquitos swarm in season. No permanent human habitation has ever managed to cling and today would be illegal because the Farallones are a wildlife refuge.

There is a 130 year-old house without power or heat offering shelter for approved scientists only. It is illegal to set foot on the islands without several layers of official permission.

What is remarkable about them aside from the diversity of seasonal life forms that use the otherwise bare rocks as a way-station is the fact that the waters around them host the most concentrated population of great white sharks on the planet. They are not there year-round. They come seasonally from literally global travels. Some shuttle in from Australia’s Great Barrier Reef or Southeast Asian trenches. Some visit from unknown waters. Females visit only every other year and no one knows why.

Then there came Susan Casey, a journalist from NYC of all places but an outdoor type who had creds from Time, Outside, Sports Illustrated, Esquire, and Fortune, among others. In this book she tells how she became interested in great white sharks, discovered the Farallones, and talked her way into being allowed on the island for a season at the research facility there and, later, on a hired yacht used for research. What happens to her, to the yacht, and to many of the people she meets along the way makes for compelling, sometimes fraught reading.

Speculation is a breeding ground exists somewhere. This may explain why female sharks are not seen every year. One lone man dives off the islands for sea urchins during her stay there, and Casey meets him. He tells stories of facing down great whites and having to hide from them in rocks and caves, hoping his air did not run out. She meets a guy who runs a cage dive tour boat; he chums to attract sharks so his paying customers can get their macho thrill, which naturally upsets the natural balance of things and pisses off the scientists.

Casey admires the very few tough, determined men who man the dilapidated house and stand freezing watch on the old light house. They do this is most weather, but some of the storms that smash the islands are not to be believed and can be survived only with difficulty and luck. This is not San Francisco weather you’ll find in tourist guides.

One of the scientists has a dream to surf one of the perfect waves in waters so infested by great whites it would be suicidal. Still, he plans. Will he actually try it? If so, does he pull it off? You’ll have to read the book.

Did you know sharks are older than trees? In this book you learn amazing things and witness spectacles from nature incredibly few have been privileged to see in person, and live. Did you know the blood slick from a freshly-decapitated walrus or seal is bright scarlet due to all the oxygen in it? Visible for miles, if you are looking for it. If your job is to scramble into small boats and rush to the fresh shark kill in hopes of catching sight of more shark hits on the carcass. Viewed at arm’s length, sometimes tagged for tracking, and on occasion curious about the shark scientists, great whites have been known to heave up out of the water to take a better look. They do this with intelligence and awareness of context.

The victims of shark attack are also cognizant, aware, and sentient beings. Casey tells of witnessing heart-wrending sights such as the front halves of sea lions desperately pulling themselves in panic from the surf, terrified and trying against hope to survive the loss of half their body in one bite. She tells, too, of poor suffering walruses recuperating in pain from savage bites, stoically suffering as their remarkable curative powers work wonders.

Life is harsh, brutal, and brief, yet there are moments of joy, too, such as watching pods of Blue whales surge by in stately lines, or seeing Wright whales breach in seeming celebration.

Some of the sharks are female, which means bigger. The scientists have nicknamed them The Sisters. They have their own prowling zone at the Farallone Islands, as does The Rat Pack, a group of smaller males. There seems to be a pecking order, too; if a sister shows up, the others back off. We are talking sisters upwards of 40 feet sometimes. Each shark has its own personality, too. They are far more intelligent than anyone realizes and Casey writes about several shark individuals with names such as Stumpy, Half-fin, and The Hunchback. There are sharks who are all business and goofy ones that seem to frolic for the observers’ amusement. There are curious sharks and indifferent sharks.

None are the mindless monsters from JAWS, none are monsters in any way. They are survivors, intelligent and elegant, stately and charismatic. It is their charisma that dooms great whites to suffer man’s curiosity. The scientists working at the Farallones are racing against time to learn enough to be able to understand and maybe help this remarkable species survive humanity’s soon-to-end reign of terror and pollution.

Reading Susan Casey’s vivid, thrilling, and informed book is a great way to find out for yourself about one of our most amazing fellow creatures. It’s also a hell of a lot safer than going into certain waters at certain times.

/// /// ///