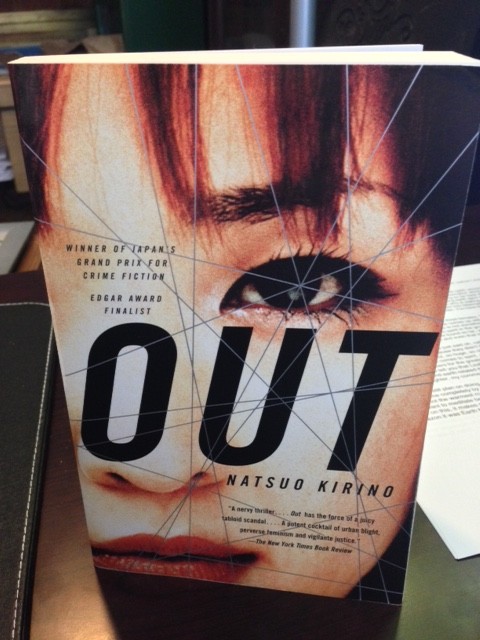

Out by Natsuro Kirino

First Vintage International Edition, Jan. 2005

Translated by Stephen Snyder for Kodansha, Ltd.

pb, 400pp, $13.95, ISBN: 1-4000-7837-7

Perhaps the title confused browsers into thinking this is a book about someone coming out of the closet in some way. It is not. Yet it is.

In it, a small group of women in Tokyo who work in a bento boxed lunch factory, on night shift to earn a fraction more money per shift, decide to help one of their own when, during a typical fight with her husband, one of the women kills.

Murder is not such a big deal to them, turns out. Not murder of a man. Males so dominate females in Japan, so unfairly exploit, manipulate, bully, and discard them, that the practical concerns kick in without much of a moral or ethical blink.

Masako Katori is the focus of this gritty, realistic, and grim novel. It is a crime, rather than a police, procedural. It lays out in unblinking detail how Katori decides to help her younger, stupider friend when that friend confesses to having killed her useless husband. Katori enlists others to help, too, and keeps them in line. They use their lunch factory skills at cutting up meat. They use their skills in packaging and distribution, too.

They dismember the corpse, put it into small packages, and discard them all over Tokyo, but one of them does the lazy thing, typical for her, and this leads to the discovery of the body. Well, parts.

Tension mounts slowly with such realism and insight into character that we read fascinated and breathless. A pall of doom seems to hang over everyone so readers tend to expect the worst.

In a sub plot that gradually blossoms into quite a touching and bizarre set of scenes, one of the men at the factory, Kazoo Miyamori, is a stalker, a lonely man of Japanese descent who was born and raised in Brazil. He is in Tokyo hoping to earn enough money to go back home and set up a business. He’s reduced to night shift at the box lunch factory, his hopes dashed. Is he dangerous or merely truculent? Is he crazy or merely strange?

That he fixes on Masako, a blunted woman in her forties who does nothing to enhance her own looks, only adds to his ominous qualities. It is while he watches her from concealment that he sees her drop some things into a sewer as she walks to the factory one evening. Turns out he investigates, and finds personal affects from the murdered man.

Pressures mount, loyalties tilt, and Masako is faced with bad choices all around. Her world has become unstable. It does not bother her unduly, however. In many ways it’s what she’s needed. She has craved something more, something different. Independence, yes, but a kind of freedom, too, found outside society. This is a clue to the otherwise puzzling title.

When gangsters get wind of how efficiently Masako has rid herself of a corpse, and offer to pay her to do the same for some of their inconvenient messes, money beyond insurance pittances enters the drama, with predictable effect. Not that Masako’s responses are ever typical; she is a surprise all along, though hardly a delight.

This story of Masako Katori is remarkable on many levels, not the least of which the damning indictment of how women are viewed, treated, and abused in Japan. This is modern industrial Japan, not some Samurai fantasy. It is presented in such detail, so matter-of-factly, and with such intense scrutiny of individual lives that we are held spellbound as we read. It’s best, we discover, to keep reading, to lop off as many paragraphs, scenes, and pages as possible with each sitting so we can pop our head up for a gasped breath when we’re done.

Women ignored or abandoned by drunken husbands intent on gambling and bar girls. Women burdened by invalid mothers-in-law or unwanted babies, left to earn the money to run the household because the husband’s wages all go to his hedonism. Women abandoned by men, beaten and left for dead by men. It’s a brutal, even savage depiction that rings all-too-true. Add to this poverty the need for menial labor that deforms the body and crushes the soul and you, too, would want out, by any route possible.

/// /// ///