A few days ago in Omaha, near where I live, a man was killed by gunfire at a park. He was driving and tried to escape the bullets by going cross-country, breaking through a split-rail fence onto a grassy field. He died of his wounds.

A few days ago in Omaha, near where I live, a man was killed by gunfire at a park. He was driving and tried to escape the bullets by going cross-country, breaking through a split-rail fence onto a grassy field. He died of his wounds.

Police immediately arrested two young men, one 16 and one 15 years of age. They at once announced a search for a third boy,12 years old. He showed up today, extradited from Wisconsin, where he’d somehow gone, perhaps helped by relatives. He is charged with first degree murder, having been part of what appears to have been an ambush. The dead man was lured to the park and into a kill zone.

Little kids killing. We barely blink these days.

This numbed lack of reaction was not always the case, not even in America. Only a few days before this latest Omaha homicide I finished reading the 1985 true-crime account, Death of Innocence by Peter Meyer. ISBN: 0-425-09080-9, 327pp, the Berkley 1986 mass market pb edition.

In Essex Junction, VT two 12 year-old girls cut through a wooded strip of land, taking a well-worn path used by most of the kids. They’d come out of the school late due to one having to stay to present a music teacher with a test. Her friend waited.

In the trees they were grabbed from behind and dragged through underbrush to a clearing where two young men, one 16 and one 15 years of age, stripped, raped, then strangled, shot with bb pellets, and finally stabbed both girls. They left them for dead under two abandoned mattresses.

No one found them.

One, however, regained consciousness and, horrifically wounded, got to her feet and managed to walk out of the woods to a railroad where workmen spotted her. They radioed what they saw and told dispatch to call the police. The girl was naked and covered in blood. She was immediately carried by a concerned man to a place where the ambulance could reach her.

“What about my friend?” she asked.

This began the backtrack into the woods, starting where she’d emerged. The clearing was found and someone spotted a sad little hand barely visible under one edge. That girl was dead.

Meanwhile the surviving victim, even as doctors worked frantically on her, managed, in breathy whispers, to describe the attackers to an outraged, unbelieving police detective. She proved both brave and mentally sharp, offering enough to start an investigation that quickly spread statewide.

As this unfolded the boys who’d done it continued with their lives as if nothing had happened until the newspapers began circulating composite pictures developed with the surviving girl’s help. Their families and friends began to know who was responsible, and one of the boys even told friends they’d done it.

This senseless crime shattered the small Vermont town’s image of itself as a peaceful haven from the violence, especially among youth, then beginning to ravage the nation’s big cities. It made people begin to lock their doors, escort their children to and from school, and show up at public events in droves to protect their kids from possible harm.

This set of crimes also set up a public debate over juvenile law that continues to this day. Prevention or punishment? Engagement or control? Lenient or harsh?

Everything was blamed, from parents, teachers, and society to TV, sugar, and music. What remained undeniable was the steep decline in restraint, perspective, and control demonstrated by each succeeding generation. Where once there might have been an exchange of harsh words, shoving matches gave way to fist fights, ambushes, and knife-fights. Guns were never far behind in such confrontations, almost all stolen from home, where they’d been kept for home safety.

Peter Meyer’s meticulous, impeccably researched account leads us through the crimes and its ripples with neither melodrama nor sentimentality. He analyzes as he goes, digging deeper than a mere recital of events, seeking context and clarity where none is likely to be found. His work illuminates our perennial dilemma: Is it age or crime that determines society’s response?

Along the way we learn many absurdities arrived at by what began as good intentions. Kids of 17 were not considered capable of crime, only of delinquency. That means everything from shoplifting a pack of gum to murder counted not as crime but only as a kind of lapse of socialization. Frowning adults talking to them was the only result. Pleading with them. These kids were lumped into state institutions not equipped to deal with them, timid thieves along with hardened, brutal punks in the same places, places not legally permitted to hold them against their will. The worst of them simply walked away, knowing their age granted impunity.

Magically, at age 18, delinquency became crime and the full weight of the legal and penal systems crushed down upon them.

In response, some states lowered the age at which criminals would be handled as if adults as low as ten, while in other places more was spent on remedial or palliative measures.

Despite its age, Death of Innocence remains a seminal work well worth reading. As the murder in Omaha last weekend shows, we have not progressed much if at all. Any intelligent analysis of juvenile crime and what to do with it would benefit from including this book.

///

Ghost shows that over-dramatize are failures. Presenting factual accounts by real people, then dramatizing their stories in a plain way, is much more effective.

Many disagree, preferring fiction, or fictional tone. That’s okay, room for everyone in the unseen realms.

Plain accounts carry more impact and interest. They are easier to relate to our own experiences. For most of us, straightforward accounts offer at least a chance of useful insights and helpful attitudes. Those others, the over-heated histrionic kinds, seek only to provoke terror and horror. Entertainment is their goal, while unadorned anecdotes give us communal voices around the fire.

UFO shows often go wrong, too, in the re-enactments. How many times have we seen the Lonnie Zamora case performed? It’s been acted out for so many shows they all blur, yet each is different. While this matters little, perhaps, it does offer imprecise impressions of something that really did happen to a real person, a New Mexico deputy sheriff no less. Skepdicks can then use these unfocused and conflicting skits and bad SFX as reasons to sneer away the core story and its implications. The punters also end up with warped views.

FIRE IN THE SKY, the movie made from the Travis Walton abduction case, is a good example of what happens. His account told bluntly what happened, and his claims checked out when investigated, but Hollywood producers said the Greys, which he also reported, “had been done” and insisted on adding scenes of surreal mothership horror, pure fiction, to soup up their film. They lied to pander, hoping for a bigger profit by appealing to the suckers.

This is fine. It’s how the entertainment game is played, sure. It also destroys any chance of plain accounts making it to the public. Whether in movies or on TV, paranormal is a genre, not an investigation. No ghost, UFO, or other paranormal event is handled with respect for fact or participant. The result is mindless nonsense bandied about as if it means anything more than a slight pay-day for cynical rich narcissists.

I’ve noticed Canadian productions tend to be calmer, clearer, and sharper in focus. Far less production, far more content. Location shooting, testimony from those involved, and sensible commentary prevail in Canadian fringe shows. Perhaps it’s due to a healthy immunity from America’s madness.

Independent documentaries often lack slickness but make up for that with gems of new information. When Michael Moore’s superb film-making skills earned him Academy Award notice, naysayers desperate to discredit him used that very skill to accuse him of manipulating audiences and facts. Had his work been crude they would have used the crudeness against him, of course, but we see how this works now.

It works to keep minds closed on either side of the paranormal debate. Each advocate skews reality to sustain a chosen, cherished illusion.

From this we see anti-intellectualism moving just under the surface, along with the delusional, anti-reality policies and actions of America’s right wing these days.

Yes, from ghosts and UFOs to sociopolitical analysis of propaganda and keeping a duped populace stupid and thus easily herded.

Josh Gates, who has helmed two excellent shows thus far, DESTINATION: TRUTH on the lamentably-named SyFy Channel and EXPENDITION UNKNOWN on Travel Channel, goes to see for himself, a good approach. He is sane, good-humored, and grounded in rationality. A member of the Explorer’s Club, he deals more often with Ripley’s Belive It Or Not reality rather than the paranormal but he has co-hosted or guested on a few GHOST HUNTERS shows with a sense of humor intact.

Troubled wrecks like Ryan Buell of PARANORMAL STATE on A&E Channel, fare worse. They tend to lock into a single view, usually fearful. Buell, for example, always seemed to end up confronting demons in his paranormal investigations. It was all about him and his darkness. Turned out he was closeted gay and had a severe cancer to deal with, and his personal demons quite obviously affected the show’s approach, interpretations, and overall morose tone.

Yes, misfits can play paranormal too. On the other side, though, we find the likes of Zak, Aaron, and Nick on GHOST ADVENTURES. Curious and lively, seeking to explore further the paranormal after being freaked out during a lark in an empty hotel years ago, these guys offer constant surprises. While the evidence they come up with may underwhelm much of the time, they know how to produce an entertaining, engaging, and varied set of shows. Their choices of places to investigate are interesting in themselves, and they present history clearly and with some wit and charm.

In ANCIENT ALIENS, everyone’s favorite hair, along with its owner/ operator Giorgio Tsoukalos, maintains interest mostly by showing to great effect the many spectacular places visited or referenced during the discussion of a forgotten global civilization and the interpretation of myth and legend in extraterrestrial contact terms. What makes many angry are the pointed questions aimed at mainstream consensus realty, the answers to which no one can seem to cite.

Anti-intellectual America is the morbidly-obese part of the Bell Curve and the outliers are almost pushed off the chart these days, when they’re not shrieking in Congress or voting to curtail reality in favor of their cherished delusions.

It’s sad to watch the empire decline, idiocy dominating as fascist capitalism becomes oligarchy and a new dark ages looms to swallow even hope of long-term, maybe short-term, survival of our species.

Of most species.

///

I live in the middle of the eastern edge of Nebraska, near Omaha. The other day we could smell British Columbia and Saskatchewan burning. Our air was hazy. Air-hazard alerts were issued twice in Omaha, so dense was this forest fire smoke. The sun stayed red all day, like a blood spot in an egg yoke.

Our world is so fragile and so much smaller than we allow ourselves to realize. Our children kill now, our air kills, water is nearly gone, food is broken and often toxic, our bodies are beyond health-care’s reach and edging into palliative desperation.

///

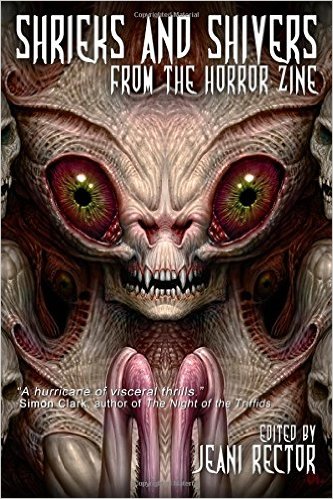

Started reading a new anthology, Shrieks and Shivers from the Horror Zine, edited by Jeani Rector. This may be her last, she says. It is going out on top, it seems. 293pp, 31 stories, an article, and a forward, all brief, is what this book contains. Majority of stories are probably under 2000 words, most about 1200 – 1500. Even your attention span won’t be strained much, noddy.

The first story, “Tapeworm” by Martin Rose, is gruesome, human, and accurate, providing a well-observed desperation anyone who wants to lose weight will recognize.

Old pro William F. Nolan, some of whose fiction was dramatized on TWILIGHT ZONE, is up next with a zinger, after which Joe McKinney gets us inside what really happened when Cronenberg filmed THE THING, especially those chilling scenes with the dogs…

There are 30 stories here, too many to cover individually, but let it be known this is unabashed, good-old rip-snorting horror, the kind you grew up reading. Choose your duds carefully, most of these are live rounds already chambered and pointed at your guts.

Too often we see semi-clever ideas fleshed out just enough to slip past harried editors needing coherent material for deadline-haunted pages they can’t pay much to fill. Magazines are scarce and the anthologies tend to be rote, based on silly themes. We hope each we buy will contain just enough to sustain our interest. We settle. Good enough is good enough.

Since when? That’s what Jeani Rector yelled, and stood against. Seeing her go is a loss to all horror readers.

Remember, a magazine or anthology has only the editor’s taste, and sometime a theme, tying otherwise disparate stories together. Well, those and the genre’s milieu, I suppose. Mostly it’s the editor’s taste, though. It had better overlap yours enough in the Venn diagram of art and commerce, or you’ll move on.

Good taste, yes. That’s what I said. We know how rare good taste is. You can find ice-cream that makes you thin a lot easier.

Brava, by the way, to Rachel Coles, for her “Nails In Your Coffin”, which is downright Poe-esque.

///

Lincoln became myth because so many wrote about him. His pivotal role and time, his character and actions, the effects of all these and more make him mythic in the way of the Caesars.

He once got challenged to a duel so, as the challenged with the right of choice, he chose swords in a small clearing with a center line that could not be crossed. His longer reach gave him advantage. At the last minute an older man intervened and stopped the duel, but he would have savaged his opponent. Think about that.

Oh, duels were illegal, too, and as a lawyer, he knew it.

As a younger man, his cruel, quick wit won him advantages over many a ridiculed political or legal opponent, but it earned him many enemies too. He later went from low- to high-road tactics, which led him to being considered a great statesman.

His anti-slavery stance came from his outrage that some gained from the hard, hot work of others. His own childhood taught him how difficult and draining physical labor was. Further, he may have equated slave owners with his father, a determined dirt farmer who drove himself and his family hard.

Lincoln rose above a hard, harsh childhood and sketchy education by reading. His early career was typical personal ambition; he was driven by a wish to escape his impoverished circumstances. Only later did he drop the greed to become thoughtful and philosophical. he was, remember, a lawyer. Adversarial law teaches wit, cruelty, and a lack of empathy that allows a kill-shot instinct.

He became thoughtful during his five years away from politics, from ages 40 to 45. Anti-slavery speeches brought him back into politics during the Kansas-Nebraska act debates. His famous speech about a house divided against itself cannot long stand was delivered during this return to political activity.

He had chronic depression, familial, and took Blue Mass, essentially pills of mercury, even early in his Presidency. He saw their effect on himself and stopped using them, to much improvement. This ability to observe, think, learn from, and change behavior let him rise into greatness, being a rare trait, especially among narcissistic politicians.

Frederick Douglas was a frequent visitor to Lincoln’s White House and taught Lincoln to grow away from ingrained bigotry, using Lincoln’s detestation of injustice as the main leverage.

He loathed injustice of any kind, another legacy, it is thought, from his overbearing father.

Lincoln’s final speech, three days before Booth shot him, endorsed black suffrage. This incensed John Wilkes Booth; was the conspiracy to kidnap and ransom Lincoln galvanized toward murder by this speech?

JFK spoke of the Gnomes of Zurich, international banksters, just before being pink-clouded, remember. Certainly speeches often signal changes many do not accept and cannot tolerate. Look how the right wing loses the dregs of what passes as its collective mind each time President Obama makes a speech.

///

Enough literary, historical, and other nattering.

Be soon and write well.

/// /// ///