Bailed out of DAUGHTER OF THE DRAGON, 1931, with Anna May Wong and Werner Toland, which kicked off a TCM tribute to Wong, and this led to some thoughts about racism, pulp, and quality.

Toland played Charlie Chan, most famously, or notoriously, but in this film he played Sax Rohmer’s arch villain, Dr. Fu Manchu. He was Swedish.

Wong facially resembled Mae West.

This movie is badly lighted. Overexposed, too. Could be a bad print. Stagey acting, too. It’s amazing how varied in quality 1930s could be.

They sure smoked pipes back then. Also had those statuettes on their desks, often with inpots or ink wells attached. Brass lamps. Humidors. Books. Letter openers. Pens. Cups. Quite a clutter.

I shouldn’t talk about desk clutter. Mine’s beyond ridiculous.

Toland was too fat for Fu Manchu. He should be, according to the books, tall and slender, and sinister, not chubby-cheeked and placid-looking. Christopher Lee portrayed him much more accurately. Even worse, Toland failed to wear a Fu Manchu mustache-and-beard combination, the facial hair named for that character. Stupid.

Not worth watching.

So many of those old-fashioned mysteries, especially the ones full of racism, end up being crap anyway, with no redeeming qualities. While Toland’s Charlie Chan mysteries are good mysteries, the underlying tone of mincing racist mockery places those movies beyond tolerance these days. You have to watch with a grain of salt in your gaze.

Often such movies wasted talent, which is the bad side of studio systems forcing otherwise good people into filler projects, just to keep them busy to earn their salaries.

Even Val Lewton, from a producer’s position, and his director Jacques Tourneur, ran up against this misuse, although they prevailed by transforming iffy projects into art.

Akin to pulp fiction.

Most was dreck. Some rose above the low-tide stain where it sloughed.

I’ve lately been impressed by the work of Robert E. Howard. Much of his Lovecraftian fiction has the advantage of clarity, for instance. Where Lovecraft affects a dated, even antiquated narrative tone so often, REH avoids density and gets on with it. Driving his plots are Lovecraftian tropes and topoi, to be sure, straight off the standardized checklist, but they are not mimicry, they are glimpses confirming outré claims. They’re outsider testimony affirming how well this stuff works. Yes, the strange books, cults, and places exist, it shouts. It’s not only Lovecraft saying so from his Providence attic, it is explorers, adventurers, and obsessed scholars.

Howard’s stories are fun to read, entertaining first and foremost, but REH usually adds the gentle caress of serious underlying themes, too.

Brings back echoes of my discover of Lovecraft in a couple Lancer paperbacks my Aunt Polly gave me on my twelfth day of nativity. It was a revelation. One of the books was a collection of Lovecraft’s own stories, The Dunwich Horror being the titular tale. The other book was an anthology by August Derleth of his own and others’ Lovecraftian stories, so I got a new writer and the awareness that his work had spawned a school, all in the same gift. I asked my aunt how she knew I’d so adore those books. “I just picked out the weirdest-looking covers I could find,” she said with a laugh.

People view me in many ways, it seems.

Oddly, I did not at once emulate HPL or begin writing in the Lovecraftian School. That was a brief phase that came later once I began collecting the monthly Ballantine mass market paperback editions of HPL’s collected work. It quickly boiled off for me, too, but the influence lingers.

A friend, Brad, got into Lovecraft’s fiction, too, and believed his uncle Ras, a scary old man out of central casting, brother to Brad’s religionist grandmother, who was keeping him alive after he’d been kicked out of his father’s house, had written a madman’s diary full of Lovecraftian hints about buried treasure and keys to opening the gates for the Great Old Ones.

Was Brad nuts?

He did show me the diary, in a tin box, masses of spidery scrawls that seemed to be the gibberish of a madman sprinkled with dire warnings and encoded hints. It was fascinating, but inter dimensional portals?

Lovecraft would’ve eaten it up.

Still, seemed outré to me, teetering on crazy, to think it meant the kinds of things Lovecraft wrote about. My inner sanity gyroscope told me Brad probably craved significance and an adventure.

Ras’s diary partly drove a wild visit to an abandoned farmhouse on the Griffiths’ farms, where I and others mocked Govaccini’s “instant obey” bullshit and got chased away by irate farm kids intent on pounding the pudding out of us. It’s now a chapter in one of my novels.

Lovecraft used empty farmhouses, lonely woods, and creepy old places city-dwellers generally avoided as his settings. This transferred to places like that in real life, so they too became Lovecraftian.

In the imaginations of his readers, such places transformed into potential dwellings for toad-like creatures, scenes of cult activity none could witness while retaining sanity, and realms of lurking, ancient horrors. Lovecraft found such places fascinating and evocative, as well as repellent. His crawling, chaotic horrors were his, written into tales of pulp excess, often in the purplest of prose.

Or so it seemed.

Reading HPL’s work as a literate adult reveals he was better and more varied than we perceived as kids. Than we were told by smug, dismissive academics. Ask Ramsey Campbell. Lovecraft was an accomplished writer nearly forgotten, saved by his friend August Derleth, who founded the small press imprint Arkham House to preserve Lovecraft’s fiction for future generations.

Yes, Lovecraft used self-conscious, excessively ornamented prose in antiquated phrasings, with archaic vocabulary, to give pulp editors and readers the flair they demanded.

Robert E. Howard did the same. As did Sax Rohmer, Talbot Mundy, and other weird tale writers. It was part of that style and sub-genre.

Compare other flavors of pulp, Westerns for example. REH wrote them and adhered to their general elements: terse dialogue, stoic heroes, lots of manly gunplay and confrontation, and much macho posing.

Lovecraft wrote no Westerns. He did write Science Fiction, Horror, and Fantasy of the Lord Dunsany type.

REH pioneered heroic fantasy, inventing Conan the Barbarian, (or Cimmerian), and the Pictish King Bran Mak Morn. He also delved into historical hero fantasy with the Puritan apostate Solomon Kane, who foreswears redemption in order to thwart evil and maybe, just maybe redeem his own sins. It’s a heady mix.

Howard was always alive to history, even as, alas, he, as did Lovecraft, honed close to racism with a razor’s edge of tone in much of his fiction. “Not of our race,” they often wrote, or “…degenerate, filthy primitives”. They set their enthralled groups of cultists apart from the rest of us, in other words, by pointing at a lack of evolved traits.

Yes, I think the Nazis would have liked, and warped — as they did with Nietzsche — his work, and Lovecraft’s, had they ever been literate enough to discover the writers’ personal correspondence. It is that cache of letters causing today’s hollow reassessment of much pulp fiction, as art is conflated with artist, as flaws are sough to justify dark accusations of racism that might fuel boycotts, even suppression.

Think of Two Black Crows or Little Black Sambo, or the distaste aimed at Disney’s JUNGLE BOOKS, DUMBO, or SONG OF THE SOUTH. All those works contain racist sequences, references, or elements. By contrast, Lovecraft and Howard, racists in real life probably more consciously than Walt Disney, who was more like Paula Deen in being oblivious, can be held responsible only for “subliminal” or “encoded” or “possible” racism.

This tendency to cite race does not spoil the stories; nothing overt shows itself in the texts.

Neither HPL nor REH were trying to preach racism. Neither included blatant racist cant in their fiction. They kept that kind of natter in their private, personal lives, where it should remain. Yes, it’s valid for scholars to examine and discuss such matters, but to see it where it is not, in the fiction, is disingenuous. It’s axe-grinding without a whet-stone.

Yes, REH especially was aware of race in history. He often cites the migrations and conquering, the invasions and wars between this or that group. He ascribes noble attributes to some, discredits other groups.

He believed evolution to be hierarchal, a common misapprehension. He therefore thought humanity in ancient times must have been inferior to us as we are now, since we are “more evolved”. This is essentially a Victorian viewpoint, inherited via a slow-to-change education system.

Since Lovecraftian fiction deals with ancient ETs seeking to regain access to our dimension of reality, it was inevitable that REH and HPL would deal with ancient people, especially their fictional ancient cultists enslaved or enteralled by the Great Old Ones. Being ancient, they were portrayed as inferior, and modern avatars of such peoples were called degenerate, having regressed, in these writers’ view, to a more primitive state.

We, more evolved, (as they’d put it), might be superior enough, if we’re lucky, to stop these ancient inter dimensional ETs and their cosmic conspiracies. Against this backdrop, Lovecraft especially took pains to remind us of Earth’s and mankind’s utter insignificance when confronted with the unimaginable vastness of the cosmos. It’s chilling stuff.

That framework, under Derleth’s aegis, became the famous, or notorious, Cthulhu Mythos. Lovecraft never meant for this to happen. He wrote only four tales solidly within this so-called mythos, and admitted he’d tossed in a few arcane references to give the stories a bit of a zing, not to bind them together into a shadowy hint at some deep state intricate cabal.

Derleth extracted tropes and topoi, cobbled up a set of extended references, and used what he came up with as a story engine to prompt a stable of writers, most of them correspondents or acquaintances of both Derleth and Lovecraft, as was Howard remember, to contribute to this shared world. It encouraged writers and sales.

It proved powerful and persuasive enough a set of images and notions that genuine occults adopted references into their esoterica.

Derleth called Cthulhu and his ilk gods, but in HPL they are portrayed obviously as extraterrestrials, of inter-dimensional origin and great age, who are regarded as gods only by their human underlings, who perform rites to “open the gates” for them to return to control of Earth. They are seen as space-faring, devious, and devoted to crushing other life forms.

Gates puts one in mind of Star Gates, the Ancient Egyptian concept of portals in the sky through which one’s spirit moved on. In fact, the Great Old Ones parallel the Greek Titans, or the Norse elder gods, just as many of the Lovecraftian names, such as Azathoth, echo Ancient Egyptian and Greek names and references. Necronomicon, the mysterious book that might be used to conjure manifestations of the Great Old Ones, breaks down as Necro = Dead, Nom = Names, Icon = Images. The book of dead names and faces, perhaps. Another echo: The Egyptian Book of the Dead.

So we see today endless pastiche of generally Derlethian view and interpretations of Lovecraft’s hints, winks, and nudges.

Aside from creepy old places, Lovecraft, and Howard with him, used dreams as fodder for his fiction. HPL’s Dunsany-style high fantasies, (high meaning set in imaginary worlds, as opposed to low, meaning set in suburban or modern venues), are eerily beautiful and definitely dream-like, from “Celephais” to “The Cats of Ulthar”. Lovecraft’s novel The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, found complete but never submitted in a drawer after his death, is a brilliant surreal masterpiece of imaginative dream-world exploration that ranks with A Voyage to Arcturus by David Lindsay and Star of the Unborn by Franz Werfel for sheer sustained invention.

It’s breathtaking.

“The Dreams in the Witch House” mingles nightmare, inter-dimensionality, and the remnants of witchcraft in the form of non-Euclidian angles from a witch long dead, which hints at ghostly goings-on, too.

In “The Music of Erich Zann” he uses discordant music and etheric, atonal sounds to transport a man into a mysterious disappearance.

In “The Shadow Over Innsmouth”, (often cited as racist due to his portrayal of the insular denizens of that town as “batrachian horrors with webbed hands and feet” — yes, tailless amphibian human hybrids), we’re shown a colony of hybrids continuing ancient rites hidden in poverty’s shade.

The point is made that Lovecraft’s fiction, using old places and dreams, shows more variety, and gains its inspiration from, a wider range of referents than simply Cthulhu and his fictional brethren.

To realize how deeply Howard Philips Lovecraft has affected literature after being nearly forgotten is to see how arbitrary influences in the arts can be. Fates seem whimsical, irrational even.

Did other geniuses vanish down the memory hole because they lacked a friend like August Derleth, or Max Brod, who refused to burn Kafka’s manuscripts as requested? Seems certain.

Was Lovecraft artificially elevated to his current status by dint of stubborn boosterism among fans?

Harder to answer, really. Certainly without Derleth, Lovecraft would likely have been either forgotten or, at best, lesser in effect for being remembered only as one of the pulp writers of the 1920s and 1930s. Derleth gave HPL the promotion that made him famous, sure, but the product had to be solid.

Lovecraft’s work proved good enough to bear academic scrutiny as well as fan enthusiasm. As did Robert E. Howard’s work. Howard, though, created Conan the Barbarian, a character as famous as Tarzan, if not quite to the Dracula or Sherlock Holmes level. He’d be remembered when HPL would probably be forgotten, with no help.

REH’s other work can be taken onto the screen to good effect. He’s not only Conan. There was, in fact, a Solomon Kane movie recently, which was acceptable but not focused enough to sustain the start of a new franchise. Yet. A new take on Solomon Kane could kick in the embrace of the fans. Who knows?

Howard’s short fiction should definitely be mined for new, exciting TV and movies. Using just his Lovecraftian stories would offer many excellent variants on an already-popular motif.

His work begs for a serious, adult approach. Give it the treatment received by, say, The Alienist by Caleb Carr, or the production values and talents found in RIPPER STREET or other BBC series, and new franchises would no doubt be born.

One short REH piece was produced, in 1961, for Boris Karloff’s THRILLER TV program, a story Howard wrote called “Pigeons From Hell”, a good pulpy title behind which hides one of the creepiest, scariest horror stories ever written. It has also jumped to graphic novel format, with Joe R. Lansdale contributing.

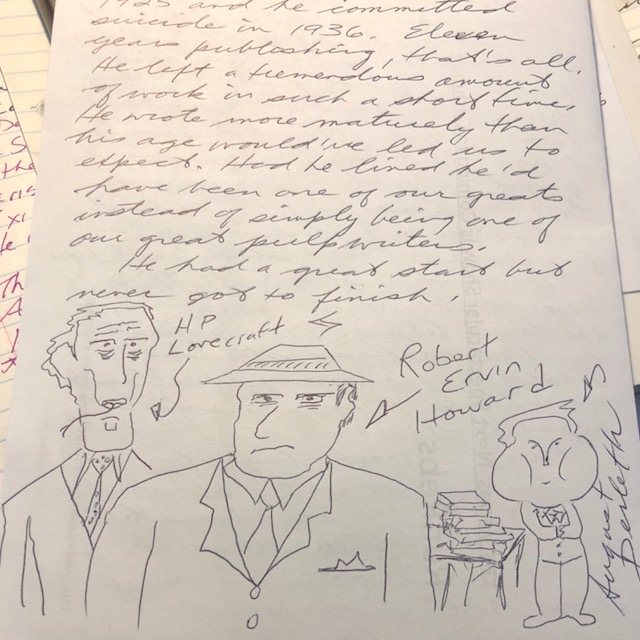

Robert Ervin Howard’s first-published story came in 1925, when he was 19, and he committed suicide upon word that his mother was dying at age 30, in 1936. Eleven years of publishing, that’s all. He left a tremendous amount of work in such a short time. He wrote more maturely over a wider range of genres and with more authority than anyone would’ve expected of so young a writer. Had he lived, he’d have been one of our greats, period, instead of being one of our great pulp writers.

He had a great start but never got to finish.

Howard Philips Lovecraft lived longer, to age 46, dying of stomach cancer. He published from 1916 to 1937, the year he died, one year after REH’s death. Arguably the more influential, HPL left a substantial body of work that continues to sell and to give scholars fodder for papers.

We’re all the better for their fiction enlivening our reading and distracting us from the real horrors. Pulp turns out to be quiet a good literary impulse, for those who swing it right.

As for Anna May Wong, her acting was better than the material and rose above the mediocrity of both racism and banality in Hollywood. Her presence was second-to-none. Again, we’re enriched.

What else is entertainment in all its forms to accomplish, if not elevating our mental lives?

Go pulp or go home.

/// /// ///