He sits writing in a notebook on a bench in the garden at Linderhof in Bavaria. The day before, the 155 steps of the tower at Neuschwannstein clamped his heart and left him in what he thought were the throes of flu that night, as he slept in the camper. Now he avoided the twenty or so more gradual steps of the cozy jewelry box palace at Linderhof. The others can explore; he’s walked through before. No need to see the bed, the tapestries, the desk in the hidden hall. Ornate to excess, it was the effete sanctuary of a man who needed discretion in his tastes.

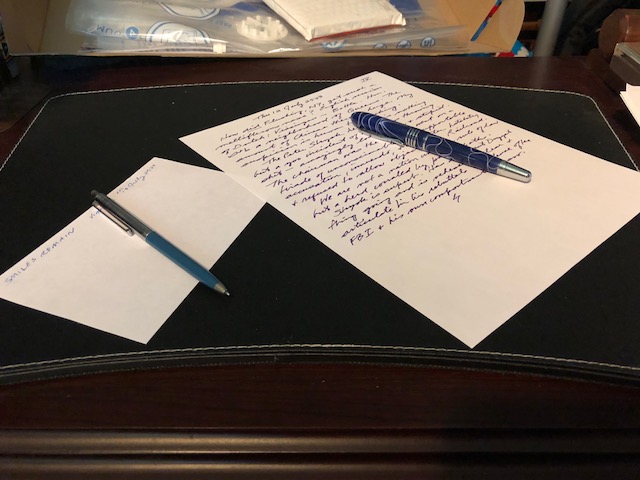

Wan sun warmed him. His notes remained coherent but amounted to random thoughts, snatched observations. Baubles he might use to decorate a fiction that had more purpose, that was his contribution to the day.

‘Are you feeling better?’

He looked up to find a woman perhaps his age, perhaps much younger. She spoke in a clear English with a slight German accent. He smiled. ‘I’m okay.’ He was by no means sure.

‘Ludwig’s tower nearly took you.’ She sat on the bench to his right. ‘Are you a writer?’

‘I am, yes.’ He closed his notebook, momentarily shy.

‘Your family seems lovely.’ Her features showed both confidence and reticence. Clear brown eyes, short brown hair, and hiking clothes on a lithe body reminded him of a student, yet if she were nearer his age, perhaps the mother of a student. He could not decide, but decided it did not matter.

So little did.

He proffered his notebook. ‘You can look, if you want.’

She accepted it and for a few moments looked through it, brow furrowed, full lower lip pursed in serious frown. ‘You write so clearly.’

He watched her, wondering what she was making of his scrawled notions, beyond the clarity of his script.

‘Thank you. Your work must be serious.’ She handed back the notebook, smiling at him.

‘They’re not comedies, my stories.’

‘Most Americans can write only inadvertent comedy. Most do not understand the serious tones of a Goethe, a Gräss, or a Solzhenitsyn.’

‘Two favorites.’

Her smile faded. ‘Is it really so?’

‘Afraid it is, yes. My favorite in boyhood was perhaps Fyodor Dostoevsky, although a fondness for Kafka has me enthralled lately.’ Take that, he thought, for seriousness.

She burst out laughing. ‘Always joking, you Americans. So happy all the time.’ She glanced past him toward the palace, where a group of tourists had queued. ‘Your family will be out soon. They will come around the side. I am glad you are feeling better today. Be slow. Take good care.’ She stood to leave his company.

He said his name and asked hers. She took his notebook and pen to jot something. ‘Write me into a story, serious American writer.’

She strolled into a crowd as his family returned to him from the gardens beyond the palace, babbling excitedly about what they’d seen, how wonderful it must be to have such wealth and privilege.

Later, as his wife drove them away, he looked.

She had written: ‘Names change, yet smiles remain.’

• • °