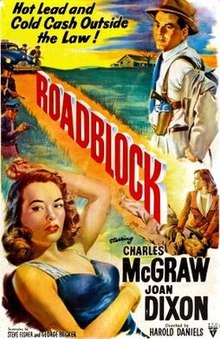

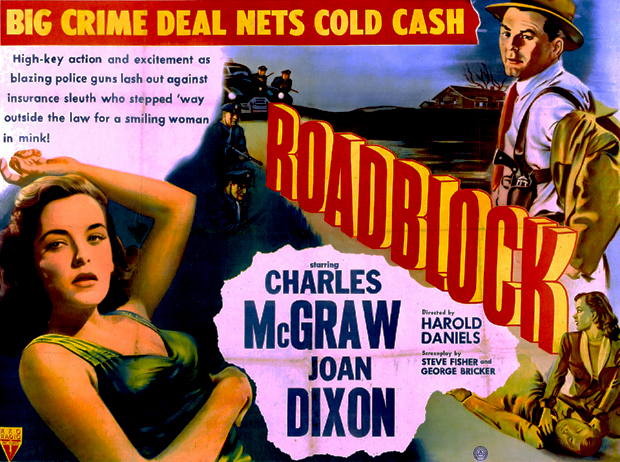

Just watched ROADBLOCK, 1950, a Howard Hughes noir. Great fun. A few plot holes but not threadbare. Scads of sharp, laugh aloud dialogue and a few twists and reversals to keep things lively. Best film from a B director who did not again get script or actor of quality. His best earner was a flop someone bought outright from the studio so he could add a graphic rape with plenty of skin to it, for peddling on the Dixie Chitlin’ Circuit. Changed the title from something ROAD to POOR WHITE TRASH and it did great.

The lesson? Even flop might work as soft porn for the right audience, as Wm. Faulkner surely knew.

TV knows this as well.

It’s ironic the industry begun and structured by D. W. Griffith’s deep literacy and reduction of classic books to basic story patterns that are used to this day should have so quickly become hostile to literacy itself and contemptuous of all but LCD pulp. Most of Hollywood’s initial money boys were illiterate immigrants who never could read even in their native languages. Reading was effete, they thought. They sought to debase literate material, dragging it to their low level. It all had to be verbal storytelling, the pitch, or visual, the moving picture, which of course at first had no sound. Cards to tell the story or add dialogue were kept as simple as USA TODAY.

We know, too, Hollywood moguls, the Croesus-Rich producers, loved to lure prize-winning novelists to studios with what to them was chickenfeed but which represented wealth to the writers, in order to torture them by a series of forced louche projects, crass topics, endless production delays, and script doctoring by a series of hacks each worse than the former. They tortured book writers.

Hemingway was well-advised to take the money and walk when Hollywood came calling.

Faulkner ended up going nearly mad from Louis B. Mayer’s torture and disrespect.

Even playwrights like Clifford Odets, a fantasia of whose torments can be found in BARTON FINK, was offered only cruelty bordering on sadism.

Yet Griffith, who invented it all, was a wide, avid reader of classics and understood storytelling as well as anyone ever did. His 3-act, 24-scene protocol remains the standard for all movies of every kind to this day. One strays from his pattern to one’s peril — no film failing to adhere to the Griffith formula does well, is the wisdom imparted by experience.

Investors know to back the tried-and-true.

This is because, by condensing the classics that had lasted for decades or even for centuries, as great tales people loved, Griffith reduced the collective rhythms of storytelling to the human essence of how we absorb stories. Narrative as formula, formula as self-portrait of humanity.

When we watch movies, we watch ourselves.

That’s what fascinates us the most. The silver screen is a Narcissus reflection and we’re spellbound.

• • °