They had a clown standee filched from a theater one had worked at. It folded in half as if bowing. Easy to transport. When they wanted, they could open it, flash the clown, fold it, and be gone.

They flashed the clown every time they drowned another one.

It was Sperry’s job to spray-paint the smiley faces. He used small cans of spray paint from a model shop his uncle ran.

They all wore black. They had black-out masks from Hallowe’en to cover their faces, too. Black gloves. When they flashed the clown it looked to anyone seeing it as if a clown had suddenly appeared. As soon as witnesses reacted, the clown vanished.

Many called the effect supernatural.

It was really just guys in black opening and shutting a folding standee, then running. Worked like slaves on speed.

Picking a victim was the hard part. Had to be one of the good-looking, academically-superior types. Brains and a future guaranteed by connections of one sort or another. Money was a plus but not a requirement.

Only pay for a kill was the thrill.

Once it became rote, some moved on, so the group adjusted. Small changes sometimes made for big differences. If all was for nothing, as they thought, then all was style. Substance could go fuck itself.

Squealing meant death of not just the squealer but his family, usually in house fires or vehicle wrecks. Two examples were all it had taken to shut other mouths. Besides, who’d tell on themselves?

Drowning the best and brightest showed even they were in over their heads. That’s part of what was intended. Discussions in car rides to and from drownings, mostly from, focused on reasons.

“How’d this all start, though?” Sperry rode transmission hump in the back seat despite his only companion being the folded clown standee. His job was to grab the standee if they had to ditch the ride.

Old cars were best. They could be abandoned or burned without qualm. Once they’d pushed one into a pond. Still hadn’t been found.

Sperry always got wired after a drowning. Manic talk, wild suggestions of what to do next, bouncing in his seat.

Conner twisted half around, left arm braced behind the driver’s head-rest. Driver was Bonacci, a level-headed planner. Conner, more a geek, wore glasses. He let them slide down his nose too much to suit Sperry. “No one knows how this started.”

“Someone’s gotta know.”

Bonacci, negotiating a swerve to avoid a pot-hole, frowned. “Maybe the old man.”

They fell silent.

#

Called the old man, he was in his late forties, early fifties. He lived by the reservoir in a rickety abandoned farmhouse. Sipped coffee constantly, scribbled in journals, and usually chased them away when they came visiting. He sometimes let them in, though. Gave them coffee. Let them smoke; few did, but it was allowed. Once he handed out stale Oreos. “Too fucking sweet.” That had been the old man’s verdict. “You can have ‘em.”

He’d had a wife, he told them. She died before he went broke burying her, same week he’d gotten fired. Moved to the abandoned farmhouse. No one had ever tried to evict him. He was grateful to the town for that.

A sliver of pension left, some cashed-in bonds and life-insurance policies, and odd jobs kept him in cheap food. For heat he burned dead-fall from the woods surrounding the place. The pot-bellied stove worked fine for the one room he more-or-less lived in. A cot in the corner, books piled around, a wobbly kitchen table that had come with the house, and an old camp percolator made of metal was all he seemed to want or need.

He was grateful if they brought pens or notebooks. They brought him school supplies, they joked. He was studying how to die alone.

#

Bonacci didn’t have to be told to steer toward the old man’s place. They stopped to take a piss into the reservoir, a tradition for them. “Enjoy,” they’d say, imagining the fish, then the town, downing their piss.

Sort of summed up a mutual disrespect.

#

“How’d it go tonight, boys?”

The old man had let them in after a few minutes of grousing and cursing. He putzed with making coffee, then sat at the kitchen table on his hard-backed wooden chair. They’d never seen him elsewhere. He had no recliner, and Bonacci had suggested maybe boosting one from somewhere, leaving it for him on the slanted porch.

No one had gotten around to following up on that idea.

The old man was gabby that night. “Best ghost-hunter I ever knew was a manic-depressive. When he was hopping, he’d get more work done than five of the rest of us. When he was down, nothing scared him. Nothing. ‘Gonna face it if it kills me and if it does, so much the better. I’ll haunt you motherfuckers once I’m cold.’ That’s what he’d say.”

None of them were interested in ghosts.

Sperry, rising up and down on the balls of his feet, waved a hand. It was halfway a school-kid asking for permission to speak. “We were wondering—“

A glare and an elbow from Conner. “Do you happen to know how the Smiley Face and Killer Clown things got tangled up?” Conner kept his hands shoved into his bomber jacket pockets.

The old man considered either the question or their faces. Maybe both. Coffee was brain food, as he often told them. “Origin stories are always bullshit, you know. Romulus and Remus my ass.”

They laughed, not knowing what he meant. Well, maybe Conner, who actually read books with just words in them.

“We were just wondering, y’know?” More Sperry figiting.

The old man sipped coffee, then sighed as if deciding to cut off his own good hand. “Guess you earned a right to know.”

Bonacci leaned forward, voice low. “You don’t have to, if you don’t want to.”

“Fucking right I don’t. Whole life adds up to that.” The old man sniffed, swiped at his nose with a forearm, then sipped more coffee. He poured fresh from the metal pot. He glared at them. Bushy eyebrows raised, then slammed down, levitation failing.

He clumped an open palm onto the table. It swayed. “First off, it’s way older than Stephen King and his Pennywise. That’s a good one, no joke, pound of flesh foolish, heh, but he came late to the coulrophobia game.”

“Cool what? Ro?” Sperry bounced off the floor as he asked.

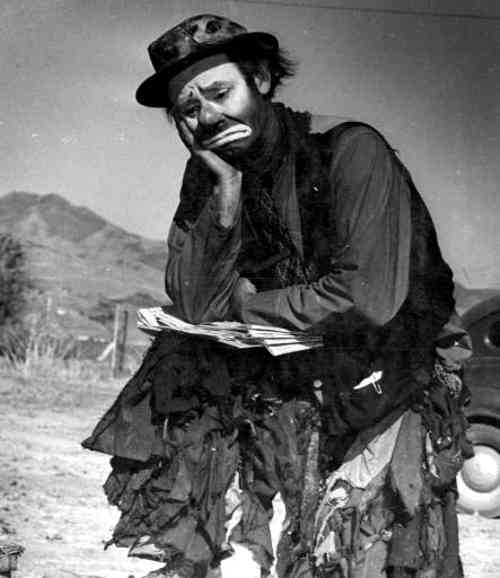

“Name for a fear of clowns.” The old man scowled at Sperry until he stopped bouncing for a few seconds. “You got to know clowns before knowing why to fear ‘em. Did you know they’re ghosts? A clown wears white-face because it shows he’s dead. He wears motley, which is the rag-tag patch-work clothes, because it’s scraps he gathers. Got none of his own anymore, owns nothing. No sharp edges on a clown’s makeup, no corners, it’s all curves because they swirl like smoke, like mist in your eyes. Great big shoes to show they’re clumsy here with us, and because they’re not touching our ground. Ever heard of a dervish?”

Conner nodded. “Whirling dervishes. Middle east mystics.”

The old man nodded. “They’re one of the roots for western clowns. It’s all about the Other.”

“Other what?” Bonacci shifted, his voice soft.

“Other worlds. Other types of being. The Djinn. The Faerie. Not human. Ghost. That’s our word but you get the idea from it. Other side of existence. The unseen one. Clowns represent all that. And they amuse us to distract us while they steal our souls. Little kids are the easiest.”

Conner digested, processed, and nodded. “So they were always kinda scary, behind the pratfalls.”

The old man’s eyebrows levitated again. “Pratfalls. Listen to you. Fencing with me, boy?”

“No, sir.” Connor shook his head and broke eye contact.

“Best not. I’d shred you inside half a minute. You don’t out-lecture an old professor. You don’t throw vocabulary words around like confetti, either.”

“Yes, sir. I’m sorry.”

The old man broke into a cackle. “Just breaking yer balls a little, son. Don’t take it big.”

“Take nothing big,” muttered Sperry, repeating one of their watchwords.

“A clown got caught with a little kid at a, let’s say a smaller venue. Small city, on the circuit, but caught diddling a kid meant run or be lynched. He ran, quit clowning for a good long time. Took it up again when he was older, charity stuff, kid’s hospital, birthdays, mall openings. Pure crap to get by. That’s when he started killing, too.”

“How long ago was this?” Conner had perked up.

Another scowl. “Doesn’t matter. Any time will do, from Ancient Rome to yesterday. Hated kids, see. In his mind, they’d tempted him, they’d betrayed him, they’d ruined his life. Couldn’t even hide as a circus clown any longer. So his hate got violent and he’d rape and kill at will.”

“We supposed to be raping them, too?”

Conner and Bonacci swiveled to glare at Sperry, who shriveled, smile burning off as he muttered, “What?”

The old man ignored it. “Smiley Face was from college. A disgusted professor, a student who’d lost his free ride, who knows for sure? Fraternity prank gone too far, or a hazing, or maybe a test or hurdle to get you into some sick club. Those are what others might tell you.”

“John Wayne Gacy.” Conner offered the name like hand-feeding a tiger. “Was he one?”

“Killer clown, sure. Nothin’ t’do with smiley faces. Just kitsch art.”

The boys remained rapt, not quiet catching the signal.

The old man said nothing for a good minute. “Couple cops, New York, retired. They think it’s a serial killer cult. Wonder if they’re right?”

He took a few gulps of coffee, his gaze going distant, sad, and grim. “I can tell you I heard once it was an anti-fraternity. This anti-frat was set up to counter the rich boys and their connections by killing off as many of them as feasible. Supposedly it spread across the country by word-of-mouth. That one makes a sick kind of sense, considering how everything’s going completely to the lowest common denominator these days. Everybody wants to hit back at the fucking one-percent.”

“Makes sense.” Bonacci to himself.

The old man shook off the momentary gloom. “Anyway, it wasn’t long before clown sightings started matching up to smiley face murders. Of course, the employed cops keep ignoring such links. It’d make their job harder, make them look like the fools they insist on being. All they do is protect rich people’s property. Ever heard of a cop preventing a crime? No, they hunt criminals after. Apply the rules and laws like brown-nosing school-yard thugs. They think they can bully and shoot everyone into conforming.”

“This is where we came in.” Conner smiled. “Like they used to say about movies, when you could go in any time of the showing, not just the beginning.”

Nerd talk kicked in.

“Hitchcock started the policy of no admissions after the film starts, with PSYCHO, so the surprise switch of lead actors would’t be ruined.”

Sperry, back to his up-and-down self-stim routine, laughed. “You guys both sound like teachers or something.”

The old man and Conner cut off their discussion of cinema.

“Anti-Intellectualism feeds into it, too.” The old man got up to make another pot of coffee. They’d never seen him take a piss.

Bonacci leaned over and put a three-pound bag of coffee grounds on the table. He’d had it in his jacket.

The old man feigned not noticing but opened the bag, smelled deeply from it a few times, and used his scoop to fill the percolator’s basket. He glanced at Bonacci, winked. That counted as a thanks.

Tires on gravel sizzled outside and they glanced at each other.

No one else said a word or moved.

#

Lone sheriff’s deputy. Brave guy. Fearless, or showed no fear, which added up the same. Stood in the doorway as if too big to force his way in. He’d do just that if he wanted. “Someone saw your car.”

Conner had zipped his leather jacket up to the neck. He stood sullen, glaring at the floor about a foot in front of the cop’s boots.

Bonacci shrugged. “It gets seen a lot.”

“It is yours?”

“Yeah. It’s mine.” Bonacci stepped slightly toward the cop, incidentally blocking the cop’s direct view of the old man.

Sperry for once wasn’t bouncing around. He had sunk into a crouch. He looked like someone pitching pennies or throwing dice.

The cop, in his late thirties at least, flicked his gaze from face to face. “Weren’t down by the river earlier, were you?”

“See, we skipped some rocks.” Conner said this, swinging his shoulders as if to demonstrate but not taking his hands out of his jacket pockets. “Then we split.”

“Yeah, we drove up here.” Sperry bounded from his crouch, nodding.

“Didn’t see anyone down there, by the river, did you?”

Bonacci glanced at Sperry, who looked at the floor quickly. “There wasn’t anyone there but us.” Bonacci’s calm voice meant what it said.

Cop nodded. “See, tracks. Car tracks, from the tire tread. You understand? They can be matched.”

“Cool.” This from Conner, his gaze level now, sensing an edge.

“It’s being tested.”

“So, what, you’ll be able to say where we drove?” Bonacci seemed amused. “We can tell you that.”

The old man coughed and slapped a hand onto his table. “Deputy, what’s the beef here? These boys are my guests.”

“Guests.” The cop said it neutrally. He considered. “The beef is, we found that missing student. The one missing the last three days.” The cop scanned the room. “Found him drowned, skin full of booze.”

“You see booze here?” The old man sounded angrier now. “I don’t like your tone, your accusation.” The coffee smell throbbed strong now.

“No accusing going on here. I’m following up, nothing more. Car was seen, then spotted heading up here, so I tagged along.”

Bonacci tilted his head. “Been hanging outside listening?” He smirked, knowing they’d said nothing incriminating.

Sperry chose that moment to ask, “See any clowns?”

The room froze solid, a block of ice-age inertia.

The deputy’s gaze went to Sperry, studied him. “Did you?”

Sperry defied the cop’s stare as long as he could, about a count of three, then looked away. “Nah. I like the lion tamers better.”

Conner snorted a laugh. “I’m kinda big on the elephants.”

“Trapeze,” Bonacci said.

The old man sat scowling, one hand around his metal camp coffee mug as if protecting it. As if the cop might snatch it and run.

They knew the clown standee sat on the back seat. Not to mention the can of spray paint rolling around on the car’s floor. If the deputy had searched their car before coming to the door, they were fucked.

The cop did not enter the old man’s place. He did not ask to look around. After looking each of them in the face one more time, he left.

They heard him drive off.

Sperry sighed. “Think someone saw us down at the river?”

“It’s not always what someone saw.” The old man sipped coffee. “I ever tell you about when I lived down by Toomey Lake?”

They shook their heads.

The old man held up two finger. “There was two of them. Husband and wife. Older, I figured. Could see them from my porch. Other than in Winter when the snow was too deep, they’d walk down from their place next to mine. Higher up the hill, neighbors. They’d come down holding hands often as not, to a park bench someone put up. You know, so you could watch the water. See the birds. Enjoy a little breeze.”

Conner spoke up. “It was you, put up the bench. Wasn’t it?”

The old man cocked his head, looking at each of the teenagers as if to ask what had happened to him, to the world. The quizzical look faded.

“They’d sit together for hours each day, then it was only him. One day I heard a splash. Then it wasn’t even him anymore, so I took a picture of the empty bench and walked away. It was none of my business.”

“They find the body?” Quietly, from Bonacci.

“Nope. Don’t know as anyone knew to look.”

Conner got it. “No one saw anything for sure. Cops were just checking.”

The old man nodded. “That’d be my guess. Didn’t bull his way in. Would’ve, had it been more.”

Had the cop shined a flashlight into their car, he would’ve seen a piece of cardboard doubled on the back. The clown illustration was on the inside, folded on itself. He’d have to unfold it to see the clown.

When they took the semi-conscious drunken victim to river’s edge, no one had been around. They’d checked.

When they plopped the victim’s face and shoulders into the water and pressed him down with their feet, he’d thrashed and splashed only a little. Feeble drunks couldn’t fight well. No one had even gotten wet.

Still, there had been no one around to see anything.

A mile up the road, Sperry had flashed the clown once, when a car drove by. Who knows if they even saw it. He’d spray-painted the smiley face earlier, near the spot where they drowned the guy.

The others had picked Sperry up and driven to the old man’s.

They’d seen no one. No one had seen them.

The game continued.

The old man put down his empty coffee cup. He must’ve had a bladder the size of Wisconsin, was their joke. Or maybe he wore diapers. Who knew?

The old man coughed. “We’re gonna have to make some small changes.”

“What kind?” Conner unzipped his jacket, swiped at sweat on his brow. The others sweated, too. That Franklin stove radiated heat.

The old man stood. He pushed himself up using the swaying table. He turned as if to make another pot of coffee.

When he turned back he had a revolver in his hand. Four shots, despite the mad scramble at the end of the third, temporarily deafened him.

He walked over to the stove. Using a crowbar, he managed to tip it over. It came down on Sperry’s legs, which still twitched. The old man smelled meat scorching. Flames sprang up from Sperry’s jeans.

The old man walked out of the shack to their car. He opened the back door using his handkerchief to avoid leaving prints. He took out the standee and threw it into the burning cabin. He went back to the car and found the spray paint. He threw that from where he stood, then closed the car door. He looked the car over, thinking. He left it there.

“Another town, another circus.”

He hiked up through woods to a secondary road. He flagged down a ride with a concerned young man returning, he said, from a hot date.

“Me, too.” The old man winked. “Thanks for stopping. Lonely road.”

“No one uses it much any more, since the new one opened.”

“New road, you say?”

“So, whatcha doin’ all the way out here, this time uh night?”

“Scouting for Boys.”

The driver whipped his head to look at the old man.

Smiling, the old man held up the book he’d found on the dash.

“Oh.” Driver seemed relieved. “My son’s.”

“Good for a boy to learn woodcraft and such.” Flipping through the book, the old man chuckled.

The younger man, just a kid really, with a kid of his own, shuddered.

He let the kid drive him a few miles, then asked to stop so he could piss. It was a dark place in a dip near the river. He threw the gun far out. He pissed. He walked up and broke the kid’s neck, shoving him over to slump in the passenger seat. He thought about orphans, how tough they had to be if they were going to make it in this hostile world.

He drove elsewhere, leaving the body in a lonely culvert probably across state lines. Tucked him under laurel bushes.

They’d stay green and dense all year round.

He ditched the car at the perimeter of a mall parking lot, then hoofed it into the commercial zone, where he found a café serving breakfast. The old man ate a hearty meal. Left a decent tip for the waitress who’d laughed at his feeble old man jokes.

He vanished like a hobo during the Great Depression, like the clowns in the circuses that once crossed the country year by year.

Before too long there were other killer clown sightings, other mysterious disappearances and drownings of America’s best and brightest.

So much resentment and poverty made it so easy to find and train a new crew. Might have to raise his standards to sort out so many volunteers.

Nihilism sells itself these days, the old man thought.

The few remaining carneys of the world shuddered when they heard about killer clowns and smiley face crimes but none said a word, especially the clowns. Behind their death’s rictus, they quailed in dread.

Clowning had always been a refuge for hardened types. Masked faces of wanted, worried men making kids laugh for their unsuspecting parents went slack and mean once the greasepaint came off.

Still, you don’t speak when you’re in white-face.

White-face means you’re already dead.

/// /// ///