Sam Clemens wrote well but lost interest in many of his stories before finishing them. “A Ghost’s Story” is a good example. This led to strong openings, silly middles, and tacked-on endings. When interest stayed strong throughout, he produced masterpieces.

He wasn’t above inserting other work to pad. The middle of Huck Finn is a digression in different tone focused on the Duke and the Dauphin, and could easily be cut. As a novella, Huck Finn would be all the sharper without that bloated middle that makes it a full novel.

Yes, there are valid points made in the Duke & Dauphin section but they’re not central to Huck’s education and growth, other than to expose him to abject cynicism and evil’s genuine banality.

Part of the trouble is, Huck Finn introduced a new discursive narrative to fiction. Gone were formal constructions, fancy sentences and pages-long paragraphs. Gone were de rigeur tropes and topoi. In their places? Someone talking in vernacular. The way real people talked was elevated to art.

There is little evidence Clemens planned this.

He just did what felt right at the moment.

Twain’s approach remained ad hoc through his life. He did what he wanted and stopped if it bored him. His attitude was the inverse of Hemingway’s or Graham Greene’s intimidating, iron-willed dedication to producing a certain number of words per day. Discipline wasn’t in Sam Clemens’s wheelhouse unless he was piloting a riverboat.

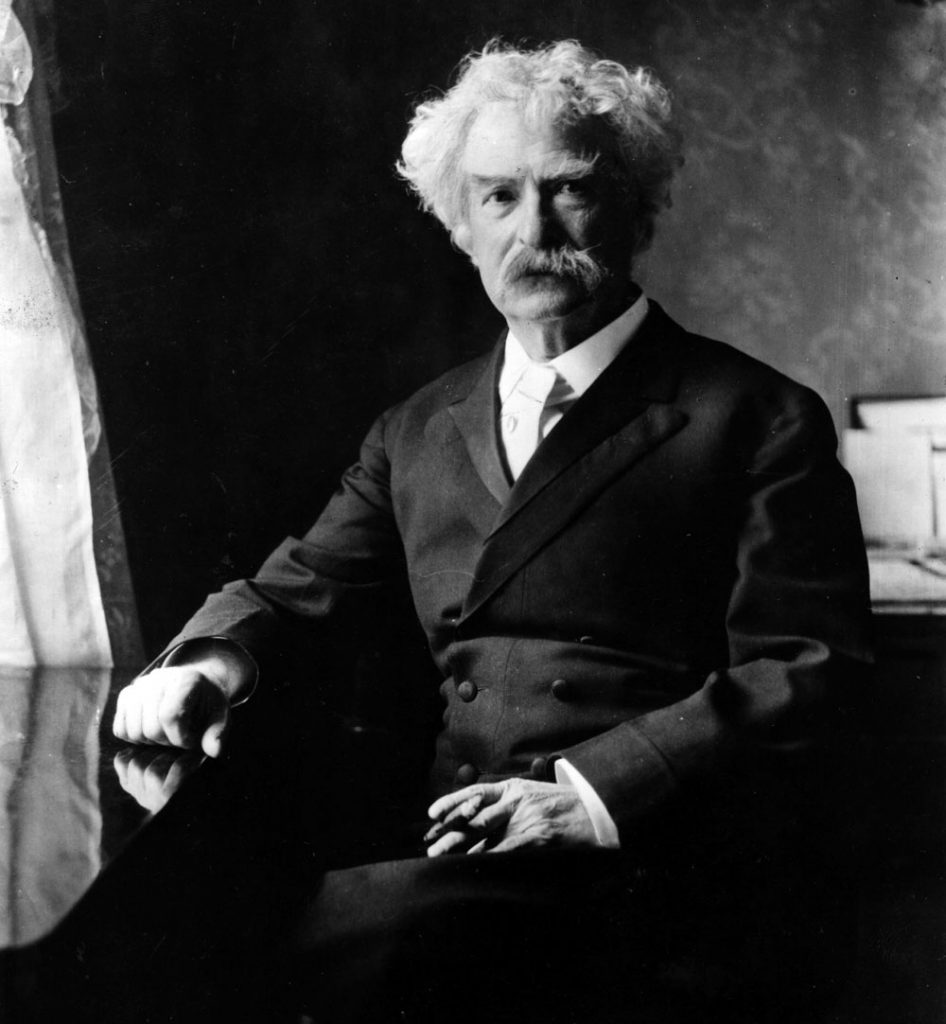

By many accounts Samuel Langhorne Clemens was a narcissist, though not a malevolent one. Self-regard remained high all his life. It was a source of strength and a fatal flaw, depending on circumstance. He made a fortune several times in his life through confidence, first in writing, then by inventing what we’d now call stand-up comedy, and finally by taking on the persona of a statesman of letters admired by all.

He lost fortunes investing in publishing, inventions, and schemes, a sucker for the Sure Thing. Striking it rich, which he’d failed to do in California’s gold fields during his brief stint there, seemed to haunt him, perhaps to drive him, despite his success in writing and his eminence in literary circles. Further, the public adored him.

His readers loved him until he turned bitter, as all intelligent writers tend to do. His work from later years, vicious, cynical satires for the most part, or sarcastic tall tales intended to shame and mock what he had christened The Gilded Age, turned away readers who expected Mark Twain to be funny only. Where had the jumping frogs gone?

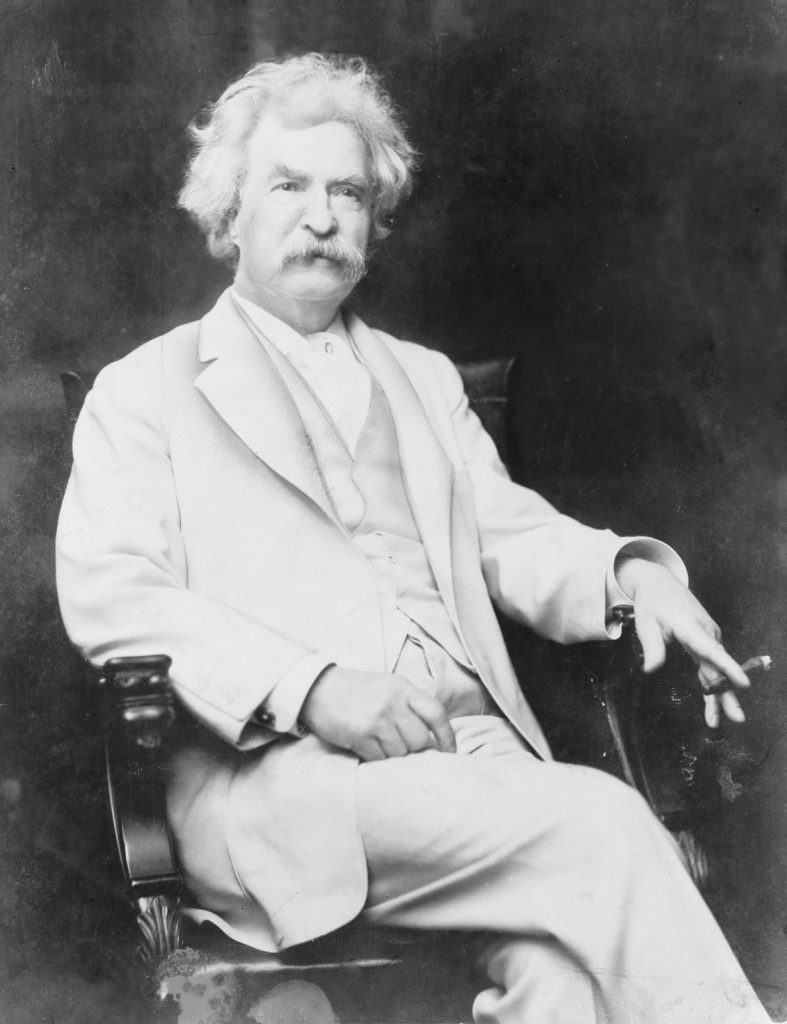

Clemens brooded, and carried a dark depression inside his white suit, white hair, and smoldering cigar. He detested robber barons and the state of the poor in such a lopsided economy yet was rich himself, off and on, and strived to make a foundational fortune he could leave as a legacy.

How much of Sam Clemens was Mark Twain is difficult to discern. As with all public personae, Twain contained much of the original, yet emphasized and edited toward calculated ends. As with Hemingway’s machismo, which ultimately subsumed his aesthetic delicacy with detail and his astonishing precision of communicating experience, Clemens found Twain a refuge, a shield, armor, but ultimately a prison. Few could see past the wild white hair, bushy eyebrows and mustache, or the twinkling eyes set across the bridge of that hawkish nose.

Anyone who becomes an icon discovers the confines of bronze busts claustrophobic. “I’m not John Beatle,” Lennon often insisted. To the public, though, yes, he was John the Beatle, and could never shake that.

Typecast is the term from acting. Once you’re, say, a monster, such as Boris Karloff or Ted Cassidy, you’re stuck in make-up, lurching at the last girl and never quite dying. Some actors, Johnny Depp prime among them, escaped a pretty-boy image by diving into strange roles. Others, such as Gary Oldman, use their character skills to hide in each role, often unrecognized.

Writers tend to use pen names. A nom de plume, or pseudonym, is but a fake name to hide behind. It was easy before the internet. It’s almost impossible today. It took a few years for Richard Bachman to be revealed as Stephen King but the John Galbraith mask came off J. K. Rowling almost at once. Today writers often use alternative names to distinguish one genre from another. This lets them write to audience expectations with no confusion. Those who like mysteries know one name, those who prefer romance, another, and so on.

In Sam Clemens’s day a pen name might have worked to get his darker material in front of readers but his ego remained too involved for such shenanigans. He was, as one biographer once put it, “proud as a boy of his day’s output”. This led him to attach his name like a brand, every bit as flamboyant as John Hancock’s famous signature.

He lived life on his own terms. Whether he saw himself as success or failure probably depended on the category of inquiry. He ghost-wrote Ulysses Grant’s biography, produced the single pivotal novel in American literature, Huck Finn, and created a wide range of superb fiction, short and long, that explored genre as enthusiastically as Edgar Allan Poe. Yet he lost his beloved wife, was estranged from most of his family, and for many years remained isolated and morose, until a young fan wrote a letter that perked him up and drew him out of his depression.

“I came in with Halley’s Comet and I’ll be going out with it.” He said this to anyone who’d listen in his final year or so, and proved correct.

Heart attacks eventually wore him out and he died at home. His legacy is as much his life as his work, which would probably make him proud.

Of such conflict between success and failure, life and death, art and commerce, and all opposites lives are made, even those lives we find compelling.

Being torn is human.

What happens between extremes is what counts.

/// /// ///