Influence on writers of cosmic, or weird, horror can and should be credited to H P Lovecraft’s work. Setting aside racism, his work touched on a cold existential view of mankind, Earth, the Solar system, even the Milky Way Galaxy, as insignificant. Set in Lovecraft’s context, our world is trivial, barely a fleck. HPL’s view takes Copernicus and explodes any notion of being central or special at any level. It reduces our history, heritage, and heroism to less than dust in a Solar wind.

Lovecraft’s horror is rooted in science fiction’s speculative glance into the void of infinity, and is firmly rooted in the science of his, and our, day.

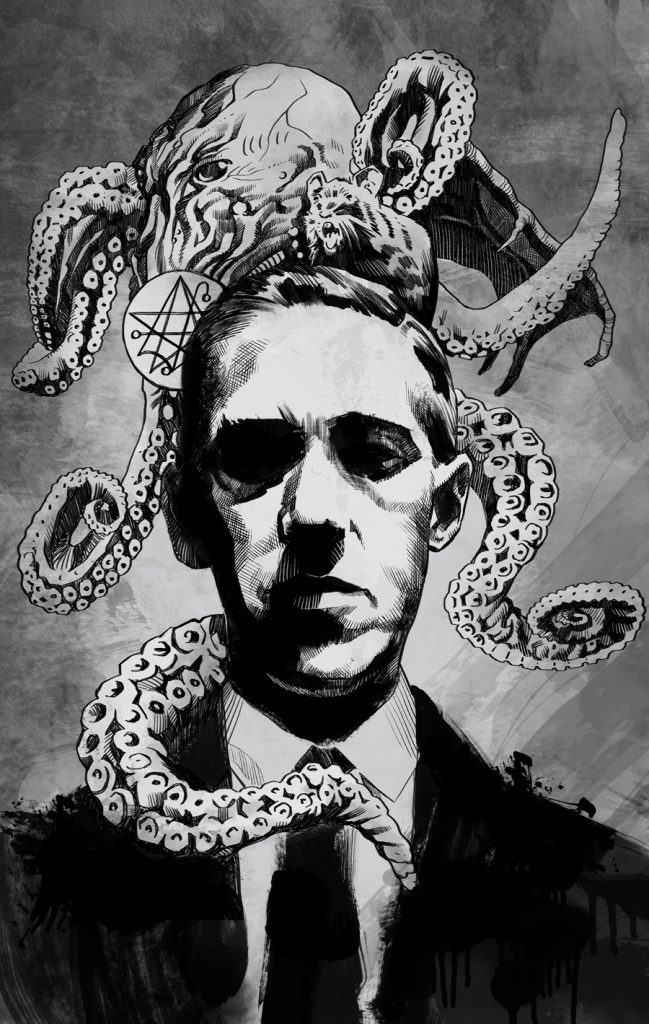

If this isn’t horrifying enough, he inhabited the Great Indifference with creatures of crawling chaos, monsters of entropy, bestial forces of negation in tentacular rampage against us, out to obliterate all sentient life-forms but themselves. Saberhagen’s Berserkers are the spawn of Cthulhu. Lovecraft made nothingness a personal adversary, a ceaseless predator stalking us, a nemesis we cannot comprehend, let alone hope to escape.

At the core of HPL’s work is the biggest FUCK YOU to humanity he could muster, and it still packs a wallop.

He didn’t cancel only culture, he put a stop to everything. Lovecraft was the literary heat death of conceptual universes.

Quite an influence, this nihilism of his, this hateful, bitterly resentful refusal to concede a scintilla of hope or dignity to our struggles for survival. No, he bellowed in purple prose: the Hostile Universe will expunge us no matter what we do and trying to comprehend it sends us into madness.

His was a hard, harsh, uncompromising, and, face it, repellent vision.

Yet this view is celebrated, revered, studied by serious scholars. It is certainly parroted in pastiche that seems never to end, as successive generations of writers start out emulating their new-found inspiration.

His ululating madness, his eldritch ichor, poisons much contemporary horror and taints the rest. An acidic hopelessness bleeds through it all.

To escape Lovecraft’s dark spot of fearful hate would require new definitions of style, genre, and reader response. Even Edgar Allan Poe is now considered, in retrospect, Lovecraftian, in particular for his tekeli-li onomatopoeia from The Narrative of A. Gordon Pym, of Nantucket, in which Antarctica’s wastes prove a horror Lovecraft couldn’t resist.

HPL wrote a sequel to Poe’s only novel, At the Mountains of Madness, and echoed the sound Poe offered, bestowing it not on penguins or terns but on … monsters from gargantuan cities made of cyclopean stones …

As time offers perspective, HPL’s influence is inarguable, and growing, but his flaws are cast into starker relief, too. They’ve always been there. Looking past them has always been an act of willful blindness. Most of the remembered work in eerie fiction did not contain HPL’s racism, arrogance, or affected arch styles hearkening to an imagined better past.

Yes, some did, often those who’d fallen within HPL’s circle of correspondence. He wrote more letters than stories, by far, too.

You’d be hard-pressed to find prose more convoluted than that of Lovecraft devotee Clark Ashton Smith, a corespondent and friend of his, and a gifted sculptor and artist. Yet not all HPL’s prose is old-bruise purple. He wrote in a variety of styles, some clear, others opaque, depending on his mood and what atmosphere was needed in the work. Dialogue remained scarce throughout his work probably because he loathed people and wasn’t good at interacting with them.

Lovecraft found inspiration in agoraphobic fear of crowds, blind bigotry toward folks with skin darker than his own paleness, and in nightmares. Others saw in his fevered visions a great story engine, which August Derleth, a talented writer turned publisher, founder of Arkham House press, championed among a coterie of Lovecrafters eager to invent their own weird monsters and add to the Cthulhu Mythos, as it became known.

Four stories written by HPL contain references to those Elder Gods, the Necronomicon appears twice I believe, yet Derleth grew from those scant seeds a new fictional realm in which to set stories, creating a cottage industry to feed Weird Tales, Unknown, and other pulp magazines, who craved weird fiction of the Lovecraftian ilk in a harbinger of its continued popularity.

So HPL’s influence spread, stoked by Arkham’s editions of is work, which had been published to preserve what Derleth thought of as remarkable fiction that would otherwise have boiled off as the cheap pulp paper on which they appeared rotted quickly away. He was right.

Without Derleth, Lovecraft would likely remain obscure.

There are those today who think that might have been a good thing, pointing to HPL’s much-discussed racism, elitism, and xenophobia.

We should remember that some fiction from the pulp era has become harder to stomach than Lovecraft’s work. Yellow Peril propaganda in Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu stories is sickening to read today. Tarzan killing any blacks he came across trumpets hair-raising racism, and the white supremacy and eugenics underlying those works baffle modern readers.

Okay, enlighten, or woke, modern readers, a majority one hopes.

There is sexism in all-too-many Victorian and Edwardian tales, such as The Beetle by Matthew Lewis or She by H. Rider Haggard, both focused on what was known then as the New Woman, meaning a liberated female who thought for herself and determined her own life, rather than serving the all-important male as domestic slave and baby factory. For them it was truly the stuff of horror, and they depicted societal ruination resulting from such trends, even as the New Woman in their work became supernatural threats.

There is rougher, less abstract sexism in hard-boiled detective fiction from the 1920s through the 1990s and beyond. Despite interesting set-ups and intriguing mysteries, they can be tough to plow through without wincing as dames and babes are slapped around and kept under Mick’s thumb.

In context, Lovecraft’s work might not stand out from some of the worst in pulp fiction, but it stood on the wrong side of history’s fence, the one separating progress from stagnation. It defended entropy from evolution, casting shadow on enlightenment, despite its pseudo-science foundation. We’re learning better than to think categorically or to condemn in generalities as we grow as a literary culture, or so one hopes.

Eventually other influences will subsume, if not supersede, that of HPL’s work. That’s how change happens, it’s how literature expands and grows deeper. With HPL’s flaws will wither much else once considered acceptable, now seen as hurtful, harmful, and dishonest.

We can improve without self-censorship or imposed standards, but for now — during what could be an age of great change away from obsolete tropes and topoi, a shift from the once-great Old white male cisgender Ones, a scuttling out from under received inertial wisdom, leaden prejudice, and spiteful stereotypes — as we embrace diversity of experience, voice, and culture in our fiction — we can escape the slime and find horror, terror, and compelling stories without disrespecting people or dismissing alternative experiences, without appropriating culture, without negating essential equality among us all. Diverse voices can harmonize. Boots can stomp but can also wade us out of swamps.

We can scrape off as much eldritch ichor as possible so we can write toward a more human, less tainted, more humane truth.

/// /// ///

/// /// ///